“These are the times that try men’s souls,” Thomas Paine wrote near the end of the turbulent, fear-filled year of 1776.

It was the soul of a woman, however, that defiantly withstood the weight of the trial — the miraculous fight for American independence — with five children at her hip.

Abigail Adams never flinched, never wavered.

Neither the crown then nor fellow citizens today can mistake her gamble on a bold new nation called the United States.

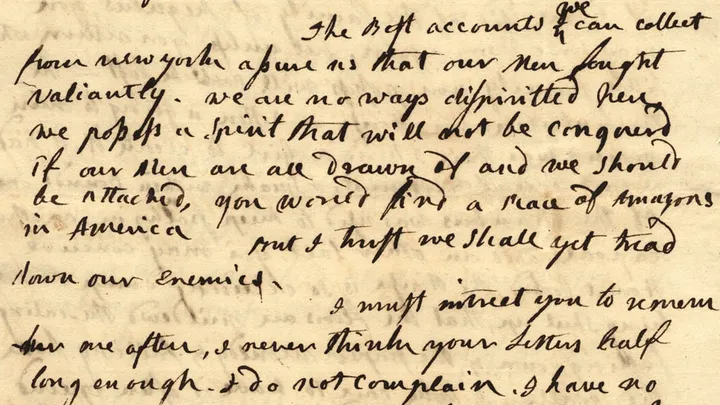

“We are no ways dispirited here. We possess a spirit that will not be conquered,” Adams wrote to her husband, John, on Sept. 20, 1776, days after George Washington’s colonial army was routed by the British in Brooklyn and Manhattan.

Adams was just 31 with five small children at her humble farmhouse, with her husband far from home for much of their marriage.

Running a wartime home without a husband by her side appeared to only fuel her defiant independence. She added in that same letter: “If all our men are drawn off and we should be attacked, you would find a race of Amazons in America.”

The now-former first lady is remembered as a gifted writer, wife and confidante of a Founding Father and the first of just two women to be both wife and mother of U.S. presidents. She was joined in that distinction, nearly 200 years later, by Barbara Bush.

“She was a revolutionary in every sense of the word.”

But as her combative words proved, the 5-foot-6-inch New England mother was harder than the granite in the hills of Massachusetts. She stands among the greatest patriots in American history.

The toughest times in American history tried Adams’ soul. The toughest times lost.

“No woman in the history of our nation contributed more or sacrificed more for our country than Abigail Adams,” said Tom Koch, mayor of Quincy, Massachusetts, where Abigail lived most of her life, and a devoted scholar of Adams history.

She rests today within the Church of the Presidents, across from his office at Quincy City Hall.

He added, “She was a revolutionary in every sense of the word.”

‘My bursting heart must find vent at my pen’

Abigail Smith was born on Nov. 22, 1744 in Weymouth, Massachusetts.

Her father, William Smith, was a Congregational minister. Her mother, Elizabeth (Quincy) Smith, was born into a prominent political family in colonial Massachusetts.

Abigail Adams’ first cousin, Dorothy Quincy, was born and raised in the community of Quincy that would later bear the family name.

The first lady-to-be married a man born in Quincy, John Adams, in 1764.

Cousin Dorothy Quincy, for her part, married another rebel born in Quincy just a few hundred yards away from her. She and John Hancock wed in Oct. 1775, only six months after the Battle of Lexingon and Concord.

Adams and Hancock had betrothed themselves to a family steeped in warrior spirit and tradition.

“The origins of the Quincy family lie in Cuincy in northwestern Normandy, France, where a knight named ‘de Cuincy’ joined the 1066 invasion of Britain,” historian Harlow Giles Unger wrote in “John Quincy Adams,” a biography of Abigail’s oldest son, the sixth U.S. president.

The name evolved to Quincy, he writes, noting that a nobleman, the Saer de Quincy, led a rebellion against John, King of England, and “appears at the signing of the Magna Carta at Runnymede.”

The two women, Abigail and Dorothy, in other words, provided the genetic link between the Magna Carta and the Declaration of Independence.

Both women bore eyewitnesses to the bloody birth of American independence.

Quincy watched the Battle of Lexington – April 19, 1775 – as 700 British troops marched on the tiny town in a quest to capture rebel munitions and her rebel beau, Hancock.

“The day, perhaps the decisive day, is come on which the fate of America depends. My bursting heart must find vent at my pen.”

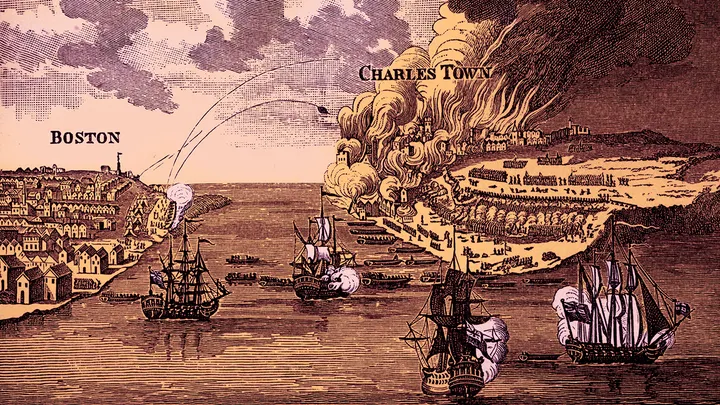

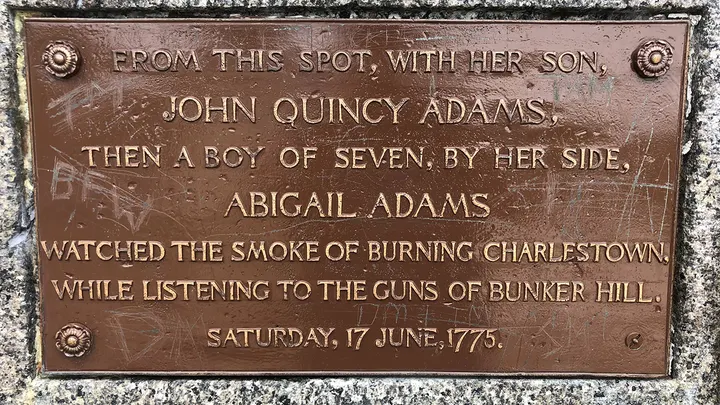

Adams watched the rebellion intensify two months later. She climbed a hill near the humble family farmhouse, which doubled as her husband’s law office, and watched the Battle of Bunker Hill erupt across Boston Harbor with her 7-year-old son, John Quincy.

“The day, perhaps the decisive day, is come on which the fate of America depends,” she wrote afterward. “My bursting heart must find vent at my pen.”

She knew a difficult life lay ahead, yet never wavered.

“While her husband was away serving the new nation, she was raising five children and running their farm in time of war,” Massachusetts historian Alexander Cain told Fox News Digital.

“The Siege of Boston was essentially outside her front door. She had to deal with inflation and food shortages and a daughter [Nabby], who was gravely ill.”

She remained devoted to American independence in its darkest hours despite enormous risk.

“She would have lost everything. Her husband would have been tried for treason, her property confiscated,” said Cain.

“But she was devoted to the cause and knew she had to set an example for her fellow women and fellow patriots. She was tough. She was absolutely tough.”

One rebellion not enough

The voluminous correspondence of 1,100 letters between Abigail and John Adams provide perhaps the most important primary source of study of the American Revolution

“Abigail (Smith) Adams did not have a formal education, but proved to be an extremely resourceful partner to John Adams,” reports the website of the Massachusetts Historical Society, the repository today of the correspondence between the two.

“While he was away on numerous political assignments, she raised their children, managed their farm, and stayed abreast of current events during one of the country’s most turbulent times.”

“Abigail Adams proved to be an extremely resourceful partner to John Adams.”

The letters, the site observes, “demonstrate her perceptive comments about the Revolution and contain vivid depictions of the Boston area.”

Adams proved her steel during the Second Continental Congress, where the delegation born in Quincy – her husband, Hancock and Samuel Adams – went to Philadelphia to convince the other colonies to join the revolt.

The rebellion was over in Massachusetts, the colony that effectively revolted against the British alone at first.

The Redcoats fled Boston in humiliation on March 17, 1776. They never returned.

The war moved elsewhere, to New York and the southern colonies.

But the stakes only grew higher. So did the fear.

But one rebellion wasn’t enough for Abigail.

The Founding Fathers understood that they sat on the cusp of an unprecedented opportunity in history, to remake a more equitable society for mankind.

Adams saw the same unprecedented opportunity to remake a more equitable society for womankind.

“I desire you would remember the Ladies,” Adams wrote to her husband in the days before the passage of the Declaration of Independence.

The two sentences that follow “remember the ladies” portray the fire of her revolutionary spirit and signature defiance.

“Remember all Men would be tyrants if they could,” she wrote. “If particular care and attention is not paid to the Ladies, we are determined to foment a Rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice, or Representation.”

“The Ladies … are determined to foment a Rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice.”

The demand represented a conviction to independence displayed by American women not often chronicled in history books, according to Cain.

“Women played a significant role in the build-up of the war,” he said. “They were the ones boycotting British goods and hosting spinning bees to make their own fabric so they didn’t have to buy British fabric. They were the ones who had to protect the home front and care for the children.”

Adams’ cry to “remember the ladies” was a demand, Cain said, to recognize the role women played in American independence.

‘Brightened the prospects of the race of man on Earth’

Abigail Adams died on Oct. 28, 1818. She was 73 years old.

John Adams lived six more years.

He died hauntingly on July 4, 1826 – the same exact day as Thomas Jefferson – the 50th anniversary of the American Independence both men famously helped forge.

The couple’s oldest son, John Quincy, was serving as secretary of state under President James Monroe at the time of Abigail Adams’ death.

She never got to see her son, the scared little boy who watched the Battle of Bunker Hill at his mother’s side, ascend to the White House — which he did in 1825.

She did not get to see her son ascend to the White House.

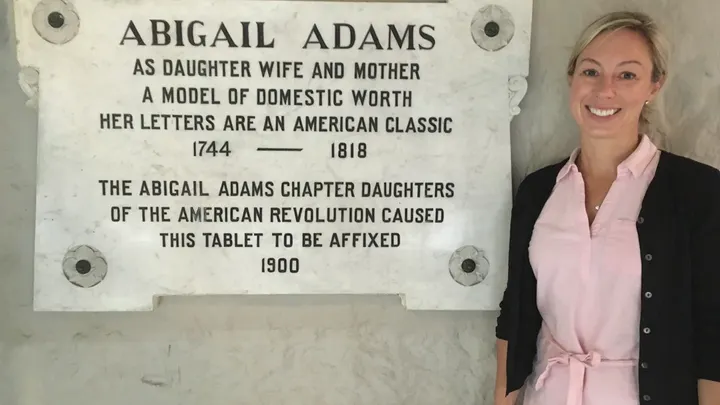

John and Abigail Adams, plus John Quincy Adams and his wife, Louisa Catherine Adams, lie side by side today in granite tombs in the family crypt in the United First Parish Church in Quincy.

It’s better known locally as the Church of the Presidents. The congregation dates back to 1639. The Rev. John Hancock, father of the patriot, was once its minister. He’s buried across the street in a nearly 400-year-old cemetery alongside 69 veterans of the American Revolution.

John and Abigail Adams moved into an estate in Quincy after the war, which they dubbed Peacefield, the name reflecting their hopes after decades of turmoil.

It’s now the centerpiece of the Adams National Historical Park, along with the nearby birthplaces of the two presidents.

The site where mother and son watched the Battle of Bunker Hill on “that decisive day” is memorialized today with the Abigail Adams Cairn, a fieldstone monument with the inscription of her words.

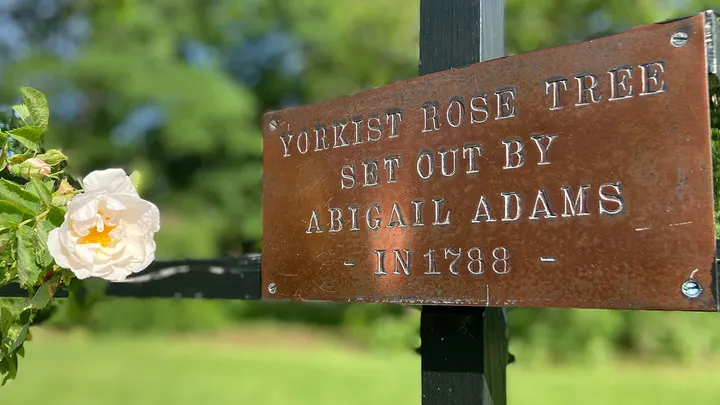

Abigail Adams has been remembered in numerous dramatic accounts and biographies. The white Yorkist roses she brought back from England after the war in 1788 and planted at Peacefield still bloom every spring.

John and Abigail Adams passed their gift for words to John Quincy Adams, who spoke or read nine languages.

He penned a tribute to his parents, scripted on a white marble tablet above the altar of the Church of the Presidents.

It captures in poetic beauty the profound gift his parents gave to the world through times that try men’s and women’s souls.

“During a union of more than half a century they survived in harmony of sentiment, principle and affection the tempests of civil commotion; meeting undaunted and surmounting the terrors and trials of revolution which secured the freedom of their country, improved the condition of their times; and brightened the prospects of futurity to the race of man upon Earth.”